How Japan’s Employment System Was Created and How It’s Changing Today

Exploring the origins of Japan’s unique employment system and the factors driving its transformation in the modern workforce.

February 18, 2025

Key Points

The Meiji Era Kickstarted Japan’s Capitalist Revolution.

A Century of Government Control Shaped Japan’s Rigid Hiring System.

The Mid-Career Boom is Breaking Japan’s Traditional Job Market.

From Samurai to Capitalists: How the Meiji Restoration Transformed Japan’s Economy

Eiichi Shibusawa(1840–1931), known as the “Father of Japanese Capitalism,” played a crucial role in shaping Japan’s modern economy. Yataro Iwasaki(1835–1885), the founder of the Mitsubishi financial group, was instrumental in the country’s industrial expansion. Their achievements symbolize the development of capitalism in Japan during the Meiji era (1868–1912).

Japanese capitalism was fully established in the late 19th century, triggered by the Meiji Restoration in 1868. The Meiji government abolished the feudal system and actively adopted Western technologies and institutions to build a modern, centralized state. Key reforms included the revision of the land system, the unification of currency, the establishment of the Bank of Japan in 1882, and the development of railways and roads. These measures rapidly accelerated Japan’s industrialization and the rise of capitalism.

The Meiji government, aiming for modernization and the adoption of Western technologies, dispatched the Iwakura Mission in 1871 (Meiji 4).

The delegation studied the establishment of central banks, joint-stock company systems, and shareholder meeting operations in the United States and Europe.

How Japan’s Unique Employment System Was Born

Japan’s modern employment system was shaped by historical, economic, and social transformations, evolving from Western-inspired capitalism to a wartime-controlled labor market, and ultimately solidifying into the lifetime employment model. This system, which established the Japanese-style membership-based employment, is called “Sōgōshoku Ikkatsu Saiyō” in Japanese and became a defining characteristic of postwar Japan.

The Rise of Capitalism and Early Recruitment Practices

In the late 19th century, as Japan sought to modernize, the government actively adopted Western financial and economic systems, laying the groundwork for a full-fledged capitalist economy between the 1880s and the mid-1910s. This period saw rapid industrial growth, driven by powerful zaibatsu (corporate conglomerates) like Mitsubishi, Mitsui, and Sumitomo.

One key development during this time was the emergence of structured hiring practices. While the origins of Japan’s new graduate hiring system remain debated, it is widely believed that zaibatsu-affiliated companies began regularly recruiting university graduates in the late 1800s. This practice aimed to cultivate loyal, long-term employees, forming the early foundation of Japan’s unique employment structure.

War-Time Labor Restrictions and the Shift Toward Long-Term Employment

As Japan entered the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937) and the Pacific War (1940), the government tightened control over the economy and labor market to maximize wartime efficiency. Businesses were placed under direct government management, corporate dividends were restricted, and companies were barred from raising funds through stock markets, instead relying on government-designated banks for financial stability.

At the same time, labor mobility was strictly regulated. In 1942, the Employee Hiring Restriction Order was enacted, requiring government approval for workers in military-related industries to change jobs. Alongside this, the government reinforced seniority-based wages, implemented regular salary increases, and introduced retirement benefits as semi-mandatory policies. These measures created a structured, stable workforce during wartime but also laid the groundwork for Japan’s postwar employment system.

The Postwar Employment Model: Stability Over Flexibility

Following Japan’s defeat in 1945, the General Headquarters (GHQ), led by the Allied forces, sought to reform Japan’s economic and employment systems, aiming to introduce a more flexible and competitive labor market. However, strong resistance from Japanese bureaucrats and business leaders prevented these reforms from being fully implemented. As a result, the wartime labor policies remained intact and became deeply embedded in Japan’s postwar economy.

During the high-growth period of the 1950s–1980s, these employment practices aligned perfectly with Japan’s rapid industrial expansion. Lifetime employment, seniority-based wages, and company-based labor unions became the defining characteristics of Japan’s corporate culture. This system fostered long-term job security, stability, and corporate loyalty—key factors in Japan’s postwar economic success.

Understanding Japan’s Hiring System: The Role of Membership-Based Employment

Japan’s employment system operates under a “membership-based employment model,” where companies prioritize long-term commitment, company loyalty, and cultural fit over specialized skills. This system has traditionally relied on three main hiring categories: new graduate hiring (Shinsotsu), second graduate hiring (Daini Shinsotsu), and mid-career hiring (Chūto).

1. New Graduate Hiring & Membership-Based Employment

Who It’s For: University, vocational school, or high school students graduating in the upcoming year.

Timing: Hiring starts around March to April of the year before graduation.

Key Features:

The backbone of Japan’s membership-based employment system, where companies hire a large group of fresh graduates at the same time.

Focuses on potential rather than experience or specific skills.

Companies invest heavily in in-house training programs, allowing fresh graduates to start with no prior experience.

Employees are hired as generalists rather than specialists, meaning they rotate across different departments over time.

Strongly linked to Japan’s lifetime employment and seniority-based promotion system, ensuring long-term job stability.

◆Why It’s Like a Membership System:

Once hired, employees are considered “members of the company” rather than just workers with specific roles.

Career progression is largely internal, and mid-career hiring is limited compared to Western companies.

Employees are expected to grow within the company, not job-hop between firms.

2. Second Graduate Hiring & Reintegration into the Membership System

Who It’s For: People who graduated within the past 1–3 years and are looking for their first job change.

Timing: Available year-round, unlike the structured new graduate hiring.

Key Features:

Designed for young professionals who left their first job early and want a second chance within the corporate system.

Companies still value potential and adaptability over extensive work experience.

Often includes additional training, similar to new graduate hiring.

Allows for career switching, since companies expect candidates to still be flexible in their career paths.

◆Why It’s Like a Membership System:

Second graduate hiring gives young workers a chance to “re-enter” the system if they made a bad career choice initially.

Employees are still expected to assimilate into the company culture and grow within the organization.

Companies see these hires as “trainable” members rather than independent professionals bringing external expertise.

3. Mid-Career Hiring

Who It’s For: People with professional work experience.

Timing: Open year-round, depending on company needs.

Key Features:

Skill and experience-based hiring, often requiring industry-specific knowledge.

Common among professionals looking to change jobs for career advancement or higher salaries.

Includes hiring for management and specialized positions.

Becoming more common as companies shift away from traditional lifetime employment.

The Transformation Happening Now

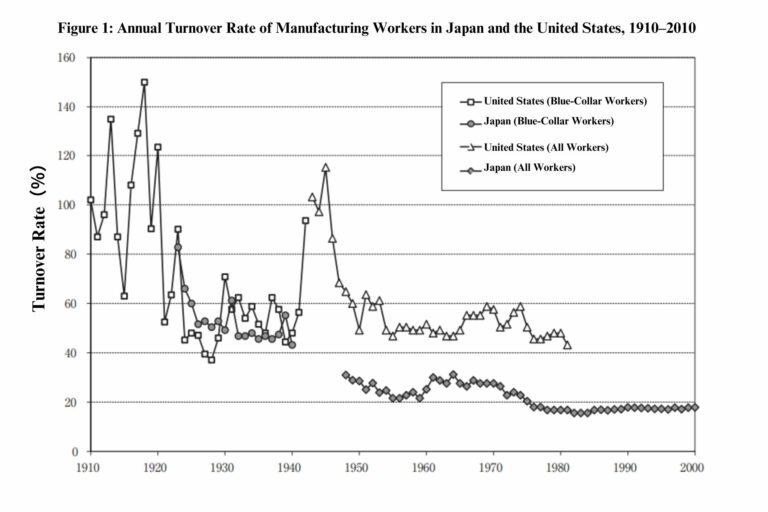

・Note: The turnover rate represents the average annual turnover rate of manufacturing factory workers (calculated as the number of workers leaving employment divided by the average number of employed workers). However, the sample size, factory scale, and definition of workers vary depending on the data source. For Japan, after 1948, the turnover rate includes regular workers in manufacturing establishments with at least five regularly employed workers, including non-regular employees.

・Source: United States: 1910–1918: Brissenden and Frankel (1921); 1919–1929: Berridge (1929); 1930–1981: US Department of Labor, Employment, Hours, and Earnings. Japan: 1923–1938: Japan Labor Movement Archive Committee (1959); 1937–1940: Ohara Institute for Social Research (1964); 1948–2000: Ministry of Labor, Monthly Labor Survey.

In the 1920s, Japan experienced a high turnover rate, particularly among manufacturing factory workers. Labor mobility was very active at the time, and skilled workers frequently changed jobs in pursuit of higher wages.

From the late 1930s to the early 1940s, the Japanese government introduced policies to restrict job changes, culminating in the enactment of the Employee Transfer Prevention Order in 1940. This regulation extended beyond the military industry, restricting the ability of workers in other sectors to change jobs freely.

As a result of these policies, turnover rates decreased, and the long-term employment system became deeply rooted in Japan, continuing until the 2000s.

Japan’s traditional new graduate hiring system has long been the foundation of corporate recruitment, emphasizing long-term employment and internal training. However, in recent years, companies have been shifting toward mid-career hiring, prioritizing experienced professionals who can contribute immediately rather than investing years in training new graduates.

A clear example of the ongoing shift in Japan’s banking industry is Mitsubishi UFJ Bank, which plans to hire 600 mid-career employees in 2024—a 70% increase from the previous year. For the first time, mid-career hires will outnumber new graduates at the bank, as it plans to hire only 400 new graduates. Across Japan’s three mega banks, mid-career recruitment now accounts for 45% of total hiring, approaching 50%.

This trend reflects a growing demand for specialized talent in fintech, AI, and wealth management, where immediate expertise is prioritized over long-term generalist development. Traditionally, Japan’s banking sector has been bureaucratic and slow to change, but this shift signals a significant transformation. Additionally, a declining interest among young professionals in banking careers and the decreasing appeal of the industry as a preferred job destination have accelerated this transition.

As a result, banks are moving away from their conventional practice of hiring large cohorts of new graduates. Instead, they are actively incorporating a more diverse talent pool, prioritizing experienced professionals who can drive innovation and adapt to the evolving financial landscape.

The transition from a new graduate-centered hiring system to a mid-career-focused labor market represents a major transformation in Japan’s corporate culture. For decades, companies prioritized loyalty, internal training, and lifetime employment, but today’s business landscape requires a more flexible and skills-driven workforce.

One of the biggest challenges of this shift is whether companies can truly embrace performance-based hiring. While mid-career recruitment is increasing, many traditional companies still struggle to evaluate talent based on skills rather than tenure or cultural fit. Moreover, Japanese corporate culture has long emphasized teamwork over individual performance, which may make the transition to a meritocratic system more difficult.

However, this change also presents a significant opportunity. If Japanese companies can successfully integrate skilled mid-career professionals and move away from rigid seniority-based promotions, it could boost productivity, drive innovation, and make Japan more competitive in the global economy.

Ultimately, the balance between mid-career hiring and new graduate recruitment will shape the future of Japan’s employment system. While lifetime employment may not disappear entirely, companies must adapt to a more dynamic and mobile workforce or risk falling behind in an increasingly competitive global market.